The Radical New Reality of Systems Science

Our Next

World View

What is a Worldview For? (part 2)

References for 'How Things Happen'

Our Survival Depends on Our Worldview's Assumptions about 'How the World Works'

-

A worldview, or Weltanschauung, is a fundamental cognitive orientation to 'how one knows' what there is to know

-

The cultures and societies that arise from this underlying orientation can appear starkly different

-

But all versions involve basic concepts and normative assumptions about 'what is' and 'how things happen'

-

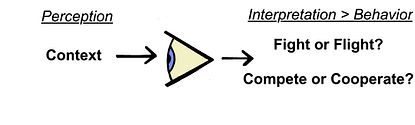

We can consider these as 'ways of seeing' then 'thinking about' phenomena, which are fundamental to a culture

-

Subsequently, such basics of 'seeing' and 'interpreting' generate assumptions about reality

-

These become a basis for social values and priorities that guide both individual and collective behaviors

-

Our survival depends upon an adequately realistic worldview that promotes effectively adaptive behaviors

-

However, the 'world as we know it,' through our worldview, is not necessarily 'the world as it actually happens'

-

If our assumptions are too inaccurate, our behaviors can become ineffective or even self-destructive

-

What then are the most important aspects of 'how the world works' which a realistic worldview must attend to?

-

Systems science differentiates two fundamental concerns for understanding 'how the world works'

-

One is predictably deterministic causality and the other unpredictably emergent self-organizing systems

-

Long-term sustainable survival would seem to depend upon a worldview that can interpret both

How We Know the World is not Necessarily How It Is

Our Worldview is not Reality Itself

We can think of a feedback loop, between 'the world out there' as we perceive it and the 'world as we know it' in our minding of it. We somehow 'take it in' then 'make it meaningful' in relation to interpretations and concepts, which facilitate assumptions and theories about it, which promote specific values and priorities we can use to guide our behaviors. We re-present the phenomena of 'the world' as our interpretations and assumptions. The specific traits and values of any particular worldview emerge from these re-presentations.

A Worldview-forming feedback between phenomena and mind that guide behavior :

However, our interpretations could be significantly inaccurate. People tend to reflexively assume that one perceives or 'sees' realistically -- that what one 'looks at' or 'thinks about' is exactly what one is 'seeing' or 'thinking' in the mind. But our minds are not 'the world out there.' Our perceptions, thoughts, ideas, are representations and interpretations of phenomena -- not the phenomena them selves. Most importantly, how we interpret our perceptions is configured not only by our experience, but by socially and culturally conditioned assumptions about 'how the world is' and 'how things happen' in it. Thus, we 'see' through our assumptions in ways that can distort our perceptions of 'what actually is.'

We assume we 'see' what is: But we 'see' as we expect to: Thus it is possible to 'see' mistakenly:

The Basic Assumptions Underlying a Collective Worldview are Culturally Derived

Much of what we seek to understand is not even overtly visible, audible, or touchable. Concepts and data obtained in other ways than our senses are required to 'make sense' of most phenomena. Society and culture provide most of those concepts and data. So 'how we know' is deeply conditioned by collectively shared assumptions -- assumptions that become normalized as 'reality.' Obviously, people often disagree about how to interpret phenomena. We do not all 'see things the same way.' Whether in personal relationships, politics, or scientific research, agreement can be difficult to achieve. What is 'real' or 'true' to one person might not be to another. However, these arguments are often about how to apply shared assumptions about 'reality' to particular issues. For example, we might all agree that events only happen because these are deterministically caused by preceding events and factors. From that basic assumption, our disagreements about how certain events happened will be about whose version of causes is more accurate or realistic. This is the sort of shared, fundamental ideas that form the basis of 'how we know what we know,' thus our 'worldview.'

Every society manifests through standards for normative behaviors. Those behaviors have a basis in shared cultural assumptions, values, and practices. These frame the ways people think about self and world, about 'how things happen,' then how to act 'for what purposes.'

Those assumptions and attitudes tend to be 'the water we swim in.' One is 'born into' and develops awareness 'through' these orientations to self and world. Consequently, we come to 'see' what we expect to 'see' and interpret it reflexively according to normative values -- often without registering evidence that there might be 'more to see' or 'other ways of seeing' it.

Thus, it is inherently difficult to even specify much less question or change those orientations. Significant changes in cultural assumptions tend to emerge from some turbulent disruption of the 'status quo' in which 'normal thinking' becomes obviously irrelevant. So long as an existing set of cultural assumptions serve to sustain a society, these can dominate for centuries, even millennia, as in the case of archaic hunter-gatherer cultures.

What is a Worldview For?

A Worldview is Intrinsically Purposeful -- It Provides the Basis for Behaviors that Sustain Survival

If we regard behavior as 'actions taken' for some future oriented goal, then behavior is fundamentally purposeful. The capacity to act purposefully involves some sense of 'how things are, how these might change, and what changes would be preferable.' Living systems manifest an impulse to preserve and promote their continued existence. Thus, these have an intrinsic purpose of adapting to their environments in ways that sustain the system, whether as a cell, a creature, a species, or a society. Fulfilling that purpose requires references for perceiving and interpreting conditions that are both internal and external to the system, then the capacity to act upon such information effectively. In a most basic sense, a worldview is constituted by an overall framework of those references, which provide the basis for purposeful behavior that can promote sustained survival.

Sustainable Survival Means Adapting Realistically

Animal survival depends upon some capacity to perceive and interpret realistically. Each creature requires references for 'what is' and how to interpret the significance of phenomena in ways that promote its own survival. It must differentiate food from not food, how to get food, and how to avoid danger. Such capacities of perception and interpretation enable it to adapt to its environment and changes in that environment. These constitute 'ways of knowing' and understanding. If these are not sufficiently realistic, if they do not enable a creature to promote its continued existence, then they can become maladaptive and prove fatal, either for an individual or an entire species. The capacity of animals to 'learn from experience' enables many to enhance capacities to adapt sustainably to different environmental factors or changes. Bears can learn to forage in human garbage cans. Orca whales learn to hunt different prey species in differing ways in different parts of the world. Humans evolved to have particularly versatile adaptive capacities, adjusting their behaviors in ways that proved adaptive in nearly all aspects of the biosphere. Such adaptive learning indicates a capacity for selective self-redirection toward more realistically sustainable behaviors. Humans are characterized by a particularly flexible and inventive degree of this capacity.

A Concept of Animal Worldview

Animal survival depends upon an organism's capacities for perceiving, interpreting, and interacting with its external environment sustainably. While much of these capacities are genetically endowed and instinctual, in more complex animals such a reptiles, birds, and mammals, they can involve complex cognitive processing that results in adaptive learning and behavior modification. Each creature requires some 'sense of self,' of environment, and of 'others,' in order to adapt their behaviors for sustainable survival. They have to be able to differentiate aspects what is relatively predictable, and how they might 'act upon' it. In addition, whether as predators or prey, or as social animals, they must sense what 'out there' has agency, or the capacity to act intentionally, thus might act unpredictably and be 'friend or foe.' It can be essential to distinguish, or 'see,' what is animate, or alive, from what is not -- then what its 'intentions' might be. Thus, we could say animals have a kind of 'evolved worldview,' roughly representing 'how things happen' or 'how the world works,' appropriate to their own capacities, their environments, and the capacities of other living entities. In some species, this 'animal worldview' involves not only genetically encoded references but learned information and inferred assumptions, both of which can change in adaptive ways.

The Conceptualized Worldview of Humans

This extremely basic concept of an 'animal worldview' is offered to help approach notions of what constitutes a human version. Humans are obviously animals. We are subject to similar issues of how to survive through adaptive behaviors within specific environments. Like other social animals, our adaptive capacities are facilitated by collective behaviors. But human capacities for adaptation are exponentially enhanced by our exceptional cognitive functions for abstract conceptualization, analytical reasoning, linguistic communication, quantitative calculation, and technological innovation. However, the worldviews of various human societies can appear significantly different and result in divergent behaviors.

For humans, animal aspects of adapting by perceiving, interpreting, and acting accordingly, appear greatly enhanced by abstract conceptualization and language. The frontal lobes or prefrontal cortex of the human brain provide humans with some enhanced cognitive capacities relative to other animals. Consequently, human awareness and mental orientation to the world involves abstract ideas and elaborate conceptual manipulation of these. Though it might not be overtly obvious, our thoughts and actions derive in considerable part from linguistically formulated concepts that constitute an explanatory system of ideas and theories about what is, how, and why. Whether having consciously articulated those ideas or not, upon reflective consideration, most people discover some 'theory' behind their thoughts and behaviors. It appears reasonable to assume that those concepts develop through an interaction of cultural conditioning and personal experience to form the basis of one's personal worldview. Thus, there is the potential for individuals to modify their version of a larger cultural worldview through their own thought and experience.

An Adaptive Worldview Provides Insight into 'How Things Happen,' thus what is possible, thus How to Behave Sustainably

From the perspective of conceptual human knowing, we could say that a sustainably adaptive animal worldview differentiates 'how things happen' through some sense of predictable causality, unpredictably emergent ordering, and system agency. Differentiating these aspects of 'how things happen' in some manner provide the assumptions that guide adaptive behaviors and facilitate sustainable survival. This underlying basis for an adaptive worldview is elaborated in the collective behaviors of social animals, and most extensively among humans. To exist sustainably, human societies must evolve shared concepts and assumptions that guide collective behaviors in adaptive ways. Accordingly, if these prove non-adaptive, or maladaptive. then sustained existence requires reassessment of those assumptions.

What Constitutes a 'Fully Adaptive' Worldview?

The survival of animal species presumably derives from creatures developing and employing the full range of their innate capacities, including those involving learning and adaptive innovations in behaviors. Evolution is viewed as 'honing' those capacities by imposing conditions that 'select for' the 'fittest' individuals. Animals need to 'know the world' in ways that fully facilitate their capacities for engagement with it. Humans, being arguably the most complex in terms of social creatures, with our highly elaborated cognitive and emotional capacities, would seem to 'prosper' best when their worldview activates the fullest range of those capacities possible. We would be our most 'fully adaptive' when our range of abilities -- mental, emotional, social, and physical -- receive the most engaging developmental stimuli. Surely, the basis for such maximal expression of adaptive behaviors must derive in large part from an adequately complex set of assumptions about reality that guide a cultural worldview and shape the social order that emerges from it.

In one sense, it seems that has been the trajectory of Western thought in promoting the well being of individuals in an equitable society. There is much evidence, however, that this goal is not being achieved, partly in the incidence of debilitating mental and physical health, partly in terms of vast social and economic equity, and especially in terms of the devastating effects human systems are having on the natural environments that sustain human vitality.

To accomplish all this, a sustainably adaptive worldview -- meaning one that keeps humans alive and prospering within existing ecological environments or habitat -- must somehow enable them to adequately comprehend the fundamental aspects of 'how things happen' so that they can operate adaptively -- to 'see' and interpret relatively realistically, then form assumptions and values appropriately. That means having knowledge that differentiates what behaviors will promote human existence as well as which ones are likely to threaten it, either in short or long term time scales. Such knowledge involves much historical memory and subsequent capacity to anticipate future events.

How Does a Worldview Remain Adaptive?

if our assumptions can blind us to the actual phenomena we perceive, then an adaptive worldview requires uncertainty about existing interpretations and assumptions to maintain its adaptive capacity. Maintaining a range of assumptions that might seem inconsistent or even contradictory is one way to 'build in' adaptive flexibility. However, if the conditions which humans must adapt to change significantly, that diversity might prove inadequate. When the survival of a society is threatened by the failure of cultural assumptions to promote sustainable behavior, the existing social order can fracture in ways that enable the emergence of new assumptions.

The 'What,' 'How,' and the 'Why' of an Adaptive Worldview: Tracking Causality AND Agency

Obviously, all animals must have some capacity to perceive and interpret physical aspects of them selves and their environments. Adaptive behavior that promotes their survival requires some such understanding of 'how things happen' through predictable cause and effect, including what each creature can do with their own bodies to manipulate their physical environments..We can call this the 'what' and 'how' of an adaptive worldview -- as in 'what things exists' and 'how do those things effect each other.' But, in addition, creatures must contend with other creatures. They must have some sense of what around them is 'merely material' versus what is 'animated' by unpredictable agency. We might term this the 'why' of a worldview. Animals must understand what entities 'out there' are potential food, possible allies, or threatening predators that can guide behavior. That constitutes some sense of 'why' other creatures act as they tend to do, especially when their actions are not predictable.

From a systems science perspective, this basic contrast of concerns can be stated as between understanding properties of matter and energy, in terms of predictably deterministic physical causality, and the unpredictably emergent self-organizing of complex systems, which can manifest self-directing behaviors or agency. These categories of 'what is,' 'how things happen,' and 'why,' are essential for any sustainably adaptive worldview to perceive and interpret. Survival from that perspective means interpretating any given context through dynamical models that differentiate and correlate these contrasting aspects of 'how the world actually works.'

But, that means interpreting some contexts, some phenomena, as 'creaturely', as having a 'purposeful why'

to its behaviors, even though it does not appear to be a particular living animal:

The Cultural Evolution of Adaptive Worldview Assumptions

The general concept of evolution as the consequence of environmental conditions that 'select for' genetic traits, which increase a species capacity for adaptive survival, can be applied to human cultures. Here, one can think in terms of "the survival of the fittest." In that view, a network of human cultural concepts, assumptions, and priorities, 'evolve' in response to a given ecological context as guides to adaptive behaviors which promote the survival of a society. For most of human history, that meant hunting and gathering behaviors suited to a given ecological context. However, once humans created their own 'tame ecologies,' based on agriculture, animal domestication, urbanized living, and technological manufacture, the conditions that selected for adaptive behaviors, or 'fitness,' changed significantly. So, the purposefulness of a worldview will likely appear differently in an ecologically embedded hunter-gatherer society than in an 'ecologically distanced' civilized one.

In reference to the notion that an adequately realistic worldview must promote awareness of both deterministic and emergent or agentic phenomena, the emphasis on these two appears to change in the shift from ecologically embedded hunter-gatherer societies to civilized ones. Within the 'tame domain' of the latter, adaptive behaviors necessarily become more preoccupied with predictive control and manipulative management of human created contexts. Consequently, the cognitive emphasis of a civilized worldview seems likely to shift more toward left hemisphere modes of attention and thinking, as these enhance manipulative control behaviors.

How is a Human Worldview Composed?

Culture as a Basis for Assumptions Underlying a Collective Worldview

Every society manifests through standards for normative behaviors. Those behaviors have a basis in shared cultural assumptions, values, and practices. These frame the ways people think about self and world, about 'how things happen' and 'for what purposes.'

Those assumptions and attitudes tend to be 'the water we swim in.' One is 'born into' and develops awareness 'through' these orientations to self and world. Thus, it is inherently difficult to specify, question, or change those orientations. Significant changes in cultural assumptions tend to emerge from some turbulent disruption of the 'status quo,' So long as an existing set of assumptions serve to sustain a society, these can dominate for centuries, even millennia, as in the case of archaic hunter-gatherer cultures.

Since the advent of civilized societies, there have been numerous permutations of cultural worldviews. Many of those have transformed over time. Some appear to have failed in terms of their long term adaptive sustainability. Currently, significant distinctions can be made among how societies around the planet conceive aspects of life and human purposes. However, in the 21st Century, the majority are operating effectively under the dominance of some basic Western European-derived cultural assumptions. These are not only configured around the control-obsessed concerns of 'survival through civilized behaviors,' but the particularly modern emphasis upon the scientific reduction of phenomena to materialistic physics and deterministic causation and the demands of maintaining a highly financialized economic system of manufacture and marketing on a global scale. All these factors promote fundamentally mechanistic assumptions about 'how the world works.'

Strangely, perhaps, that does not mean people are consistently logical or scientifically factual in their thinking. Modern assumptions about the preeminence of materialistic causation and the primacy of control are entangled in shared priorities for individualistic competition and the aquisition of relative advantage or dominance over others. In the competitive pursuit of influence, profit, and manipulation of others, people will think and say whatever suits those purposes. The point is, there is a reflexive tendency to assert the validity of one's ideas and interpretations (however illogical or unrealistic) using materialistic and causal arguments. Propositions and arguments that do not claim to explain and predict in a causal manner tend to be regarded as less significant and compelling.

How Do We Know When the Assumptions of our Worldview are Inaccurate?

Presumably, when our basic assumptions about 'how things happen' are significantly inaccurate, experience would provide us with evidence that prompts us to reconsider those assumptions. There are at least three principle obstructions to such a readjustment in one's worldview. Firstly, it can take considerable time before evidence of misunderstanding accumulates to an overtly obvious extent. Secondly, we are so accustomed to 'seeing the world' through our existing assumptions that actually noticing such evidence becomes difficult. We continue to 'see what we expect to see' regardless of what is actually occurring. Thirdly, our social and economic systems become configured around our assumptions. These systems develop significant inertia and resistance to re-orienting practices and purposes. That existing impetus tends to reinforce the primacy of dominant assumptions in the thinking of individual people. The careers of academics, scientists, politicians and corporate CEOs are all deeply 'invested' in the 'status quo' worldview. Subsequently, even when someone provides evidence that existing assumptions are faulty, 'the system' tends to ignore or actively repress such evidence. These factors can drive a society into self-destructive behaviors. So, it is most likely that reevaluation of our worldview will only occur when our misconceptions result in dramatic disruption of our lives. In the words of Albert Einstein: "You can't solve a problem with the same mind that created it." When the assumptions of our worldview create catastrophe for us, we likely must undergo a radical "metanoia," a complete change in how we think about what we have to think about.